These guitars have been done for a little while now, but I just got around to taking pics and posting them. They’re both made with Oregon myrtlewood back and sides and Port Orford cedar tops. Both great tone woods, from southern Oregon, where those trees are native. Above is a Weissenborn type. More info on it on the ‘Available’ page, or contact me if you’re interested.

The above is a plectrum guitar, a near sibling to the tenor guitar, it’s a four string conceived in the 1920’s to give banjo players an easy way to transition to guitars without having to learn new fingerings. This was at a time just before amplified instruments were born, and banjos were very popular. The plectrum banjo was intended as a rhythmic accompaniment in popular music then. The plectrum guitar didn’t take off, the Martin Guitar Company made just over 200 of them, back in the late ’20’s, early 30’s (please correct me if that number is way off), so not many made. Why did I make one? I’ve made a plectrum banjo because I wanted a banjo without the fifth string, which I love playing, so I thought I’d make a similar guitar. The body size on this is basically the same dimensions as a 000 size Martin, the scale length is 26 3/16″.

Laminated Guitar Sides:

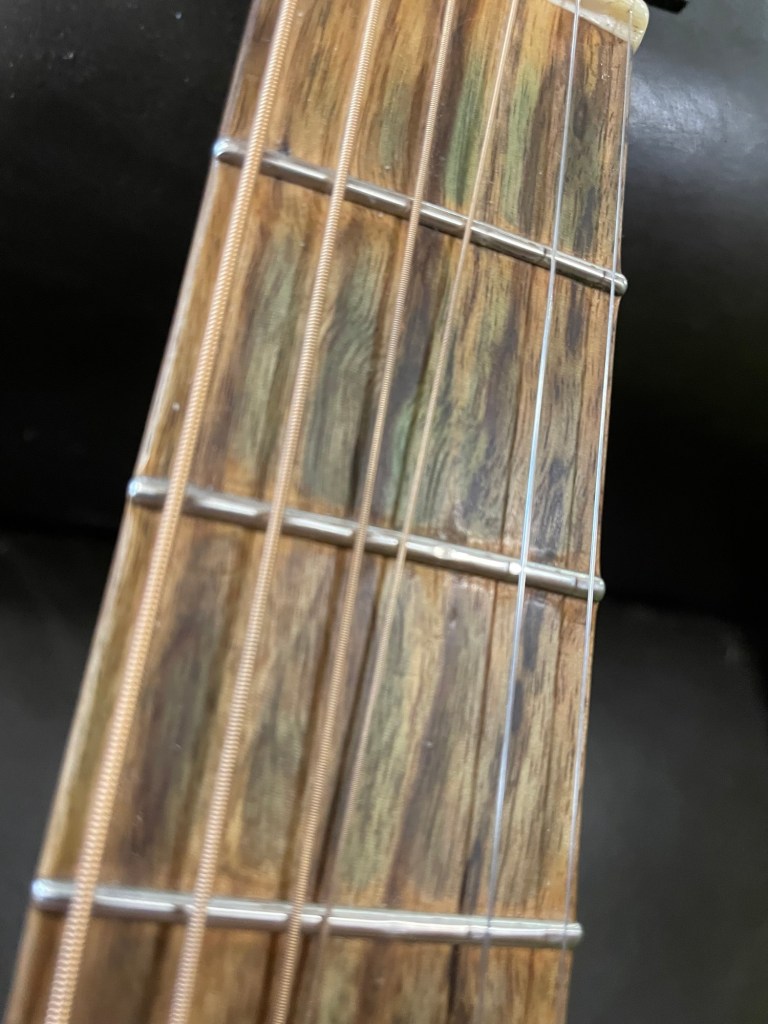

Here’s a few images of how I put the laminated sides together, both of these guitars are built this way. The Myrtle sides you see are same thickness they would be if they weren’t built this way, approximately 2mm or so. Then a 1/4″ layer of kerfed cedar next to the myrtle wood sides.

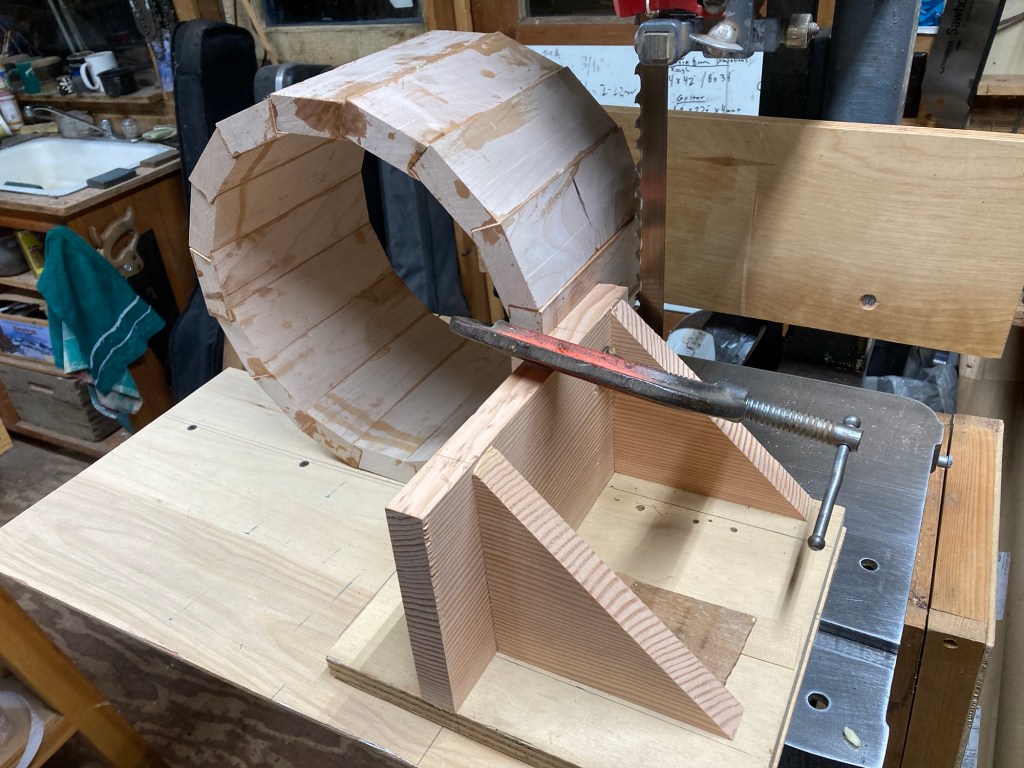

I soak the cedar for a little while in warm water, it isn’t the easiest wood to bend, hence the kerfs and the soak. I bend them on my mold with heat the same as the sides.

I use two pieces of veneer on what will be the inside to cover the cedar.

Then all the pieces get vacuum laminated on a form, I use epoxy mostly for this.

This sides are vey rigid after laminating and quite strong.

I put tape on the myrtle sides where the head and tail block will go, I like attaching them to the sides rather than the laminations. The tape facilitates removing the cedar from the myrtle. The sides are thick enough to not need a lining to glue the top and back to the ribs.

These are some shots of the added reinforcements on the tail and head blocks on the Weissenborn. The laminated sides and these reinforcements made for strong and rigid sides.